[ad_1]

The conversations at the meet and grieve downtown contrast starkly with the cheerier, hopeful talk of the picket lines.

All nine actors and writers confess their fears and disappointments and find they are not alone. Creatives are in a constant state of grief due to the very nature of their industry, having to create mechanisms to mask and cope with daily loss of potential employment, says actor Sara Fletcher.

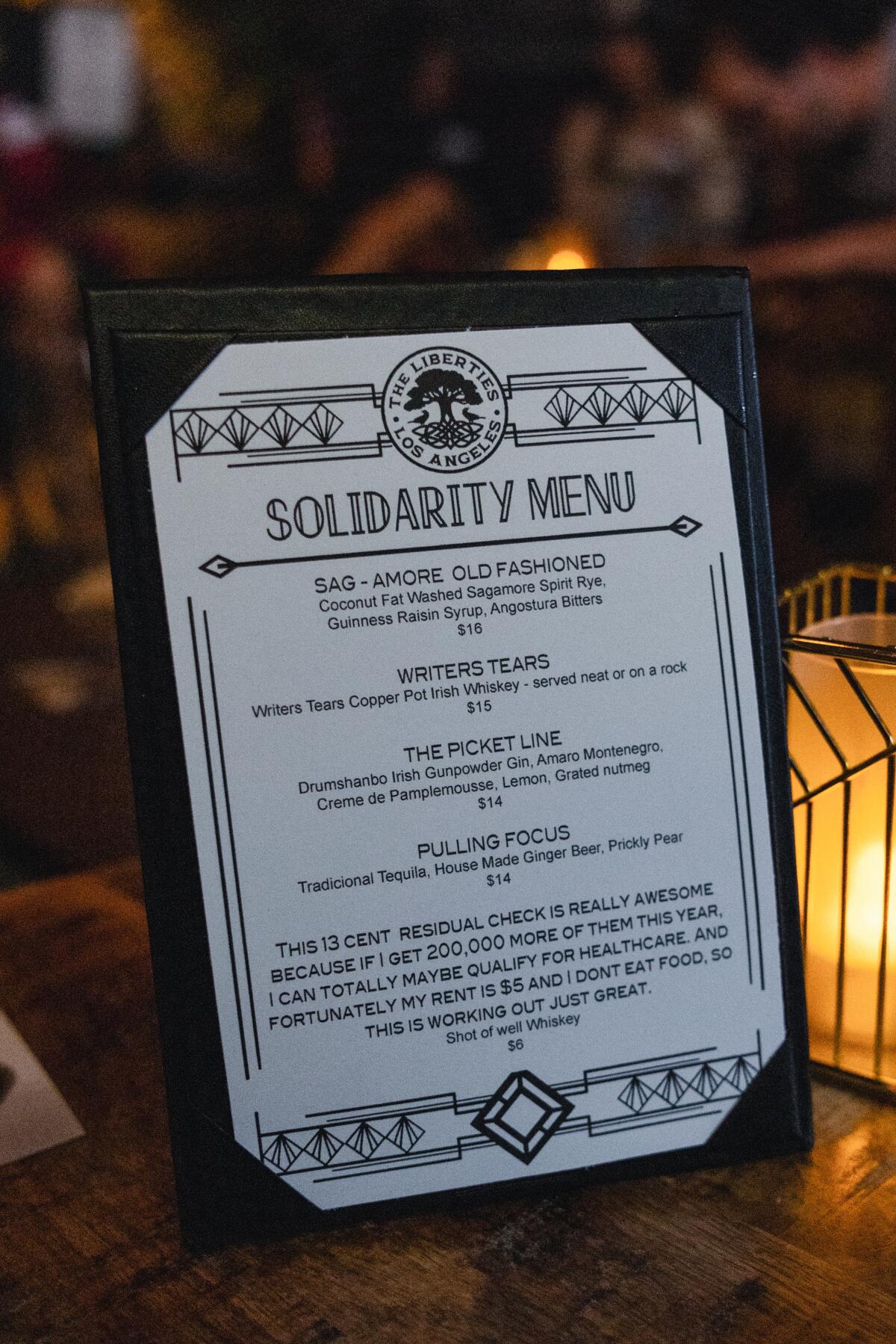

A solidarity menu of strike-themed drinks sits on a table during Grieve Leave’s meeting at the Liberties.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

“If you’re in this business, rejection is the name of the game,” says Fletcher. If you haven’t learned how to deal with rejection, “you will not survive.”

Actors and writers must pay Hollywood’s so-called passion tax, the notion that because they are passionate about their work, they should sacrifice a lot and settle for little to be successful.

“We keep being asked to pivot, pivot, pivot. We keep being asked to eat crow,” says actor and writer Brendan Bradley.

Actors and writers are often told that if they suck it up a little more, they will be afforded the career they want, but “the goal post keeps moving,” Bradley says.

Some acknowledge their complicity in creating the façade of what it means to be a successful actor or writer but take solace in the notion that the strikes are encouraging Hollywood to have honest conversations about pay.

Comedian and animation writer Annie Girard says social media misled her into believing that others were doing better than she was — until the strikes happened. Colleagues writing for prominent shows now admit that they don’t have retirement funds and that they can’t afford to have children. “Oh, so they’re in it too. They were just pretending they weren’t,” Girard says.

Rati Gupta, who found success as a recurring character on “The Big Bang Theory,” says she lost her union healthcare 18 months ago after she wasn’t able to book other SAG-AFTRA-affiliated roles.

“I was embarrassed because I was on a hit show,” she says. Hearing other friends admit that they too were at risk of losing their insurance made her feel more aware that “we’re all suffering equally, regardless of where you are in the hierarchy,” she adds.

Those at the session agreed that they wanted to maintain the sense of community that is so often absent in an industry where competition can overshadow camaraderie.

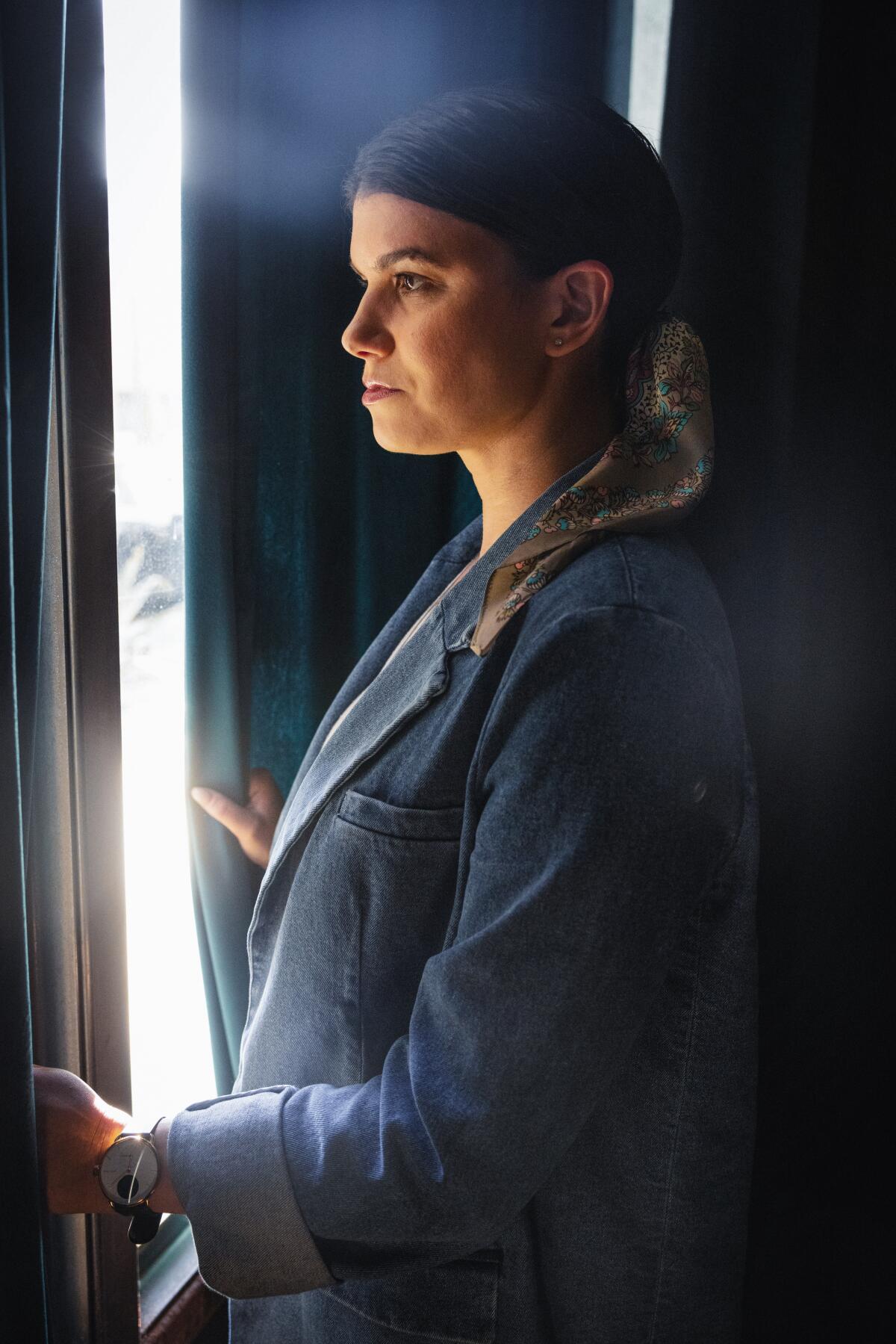

Rebecca Feinglos, a grieving educator, advocate and founder of Grieve Leave.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s so easy to feel alone in this job, in this industry,” says Gupta. “I’m scared that when [the strikes are] over, this is all going to disappear, and we’re all going to go back to being isolated.”

Feinglos asks how they are coping. Some say they are walking in nature or finding refuge in collective action like the picket lines. For Bradley, a strike captain at the Paramount Studios lot in Hollywood who is grieving his inability to promote his first film, it’s finding and keeping a routine. “I go swimming as soon as I leave the line every day,” he says.

He sees the process of striking as like working on a film set. Every morning, he drinks his coffee and drives to the studio lot, practicing talking points for informational videos he posts to his Instagram. He’s become an unintentional strike influencer and has gained thousands of followers.

[ad_2]

Source link