[ad_1]

It’s 100 degrees in North Hollywood and Roxy Rose, 60, is inside her neon studio clad in a skintight camel-colored getup, complete with her signature cowboy hat. “I’m old-school neon,” she says as she blows into a glass tube she’s bending for an upcoming piece. As a third-generation Southern California neon glassblower and signmaker, she wouldn’t dare use a blowhose, a tool new-age “benders” — the insider term for neon glass blowers — use to get air into their pieces, nor would she design a piece and delegate the dirty work to a fabricator, as some neon artists do. To Rose, being a bender is a point of pride. It’s also where she got one of her nicknames. Rose, who is trans, is lovingly called “the Gender Bender.”

With that title, she began a new era in her work, one with a fearless message focused on shining a light on the LGBTQ+ community that continues to this day. One that would be hard-fought as she carried on the family tradition of glassblowing even after her family broke ties with her upon learning she was trans. Through her art, she aims to help other trans people feel less alone and question the beliefs and systems that discriminate against them.

“Neon has always been a megaphone for anything that you want to say or idea you want to convey,” she said. “If you say it in neon, [people] will see it, they will think about it, and they will remember it. Neon has given me this amazing platform to say what I feel needs to be said.”

Roxy Rose.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

Rose has been basking in neon light her entire life. One of five kids, she was born in 1963 into a strict Christian family in the San Fernando Valley. When they weren’t in school, she and her siblings would spend time at the family’s Glendale neon shop, Alert Lighting, founded by her grandfather in 1946. The hours Rose spent watching her father and grandfather as a child paid off. “I kind of took all that for granted, neon and the process, but that also gave me a good start when I was trying to learn how to blow glass too, because I sat on those milk crates watching them for so long,” she said. At 15, Rose quit high school to work at the shop full-time, making “Walk” and “Don’t Walk” signs. Soon, she was taking home serious money. At 16, she bought her first car: a 1972 Porsche 914.

At 18, while driving at night, Rose hit a man walking in the middle of the street. He died, and although both were considered to have contributed to the accident, everything changed. She entered a dark place and began taking drugs, ending up in the hospital. A psychologist suggested she reach out to the clergy for help, which led a desperate Rose to follow in the footsteps of her grandfather again: She became an ordained minister. Like him, she began working for the church while continuing her neon career. Her parents were thrilled and introduced her to a woman from her church. Less than two months later, at 19, Rose, who hadn’t yet shared with anyone she was trans, was married.

“My only idea of a transgender person [back then] was [from] ‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show.’ I didn’t know what the hell I was,” Rose said. At age 28, nine years into what would ultimately be a 30-year marriage, Rose came out as trans to her wife, who kept her secret.

At 44, Rose bought a second home in Oregon, where she’d travel with her wife and the youngest of her three daughters. By then, her two eldest had moved out of the house. Sometimes she’d travel there alone, and in those times, she experimented with living more openly. She sought community and used message boards to connect with other trans people online. She made a promise to herself: Once her youngest was 18, she planned to come out to all her children. In the meantime, she continued working for the family business, making signage that still exists across Los Angeles and was featured in films like “From Dusk Till Dawn” and the “Porky’s” franchise.

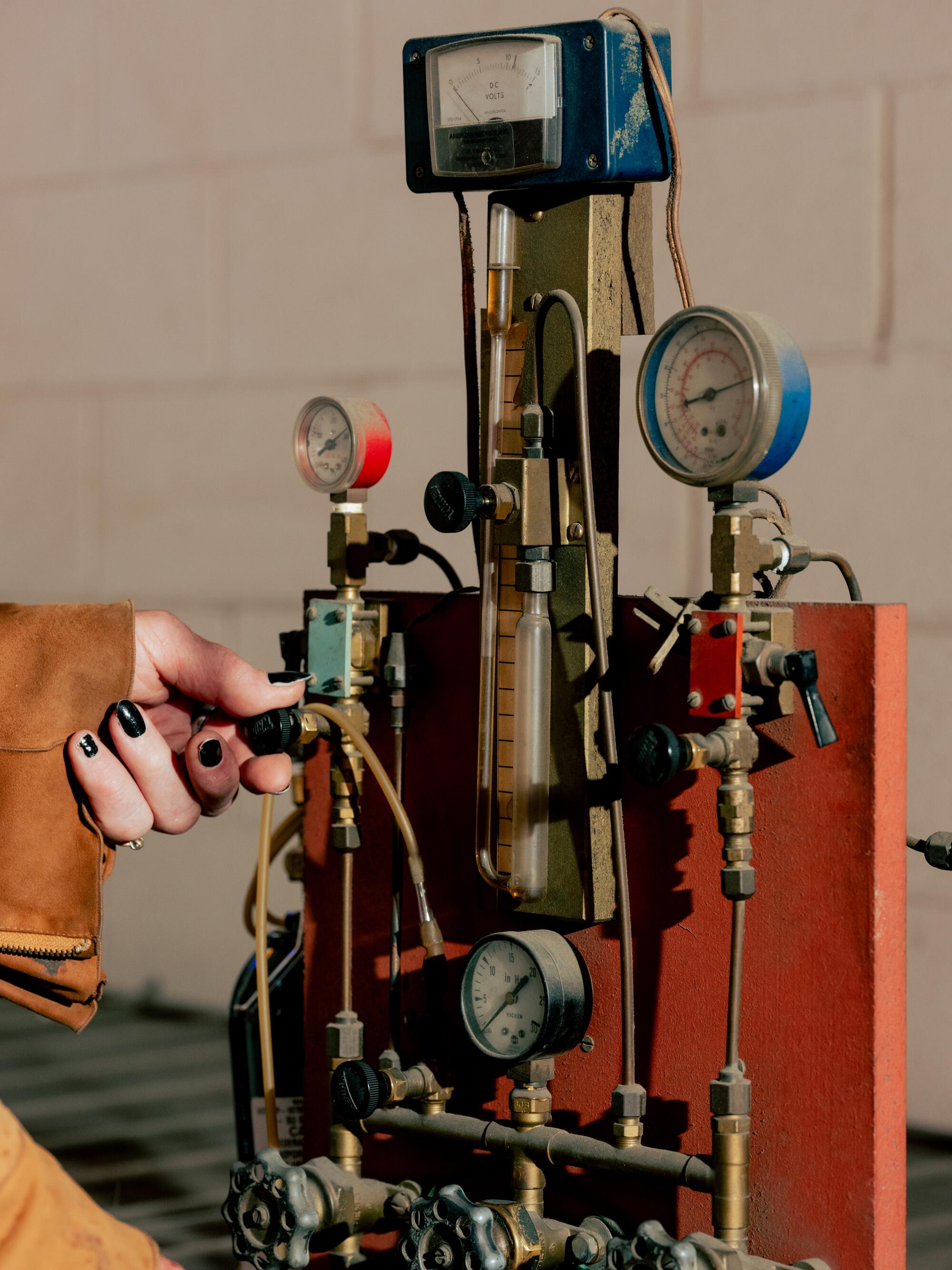

A bombarding station in Roxy Rose’s North Hollywood workshop.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

In 2009, the same weekend that Rose planned to come out to her youngest daughter, her brother, through methods still unknown to Rose, tracked down her online presence and outed Rose to her whole family. At 46, she was immediately disowned and kicked out of the business, and lost all contact with her siblings and parents. Once the news was public, her wife filed for divorce and her children no longer wanted a relationship with her. She struggled to survive mentally and financially. It was the first time in her life she didn’t have neon to distract her from her pain. “I never did anything ever in my life other than neon,” she said. “I even tried to get a job at Starbucks, but back then, being transgender, nobody would hire you.”

Rose entered a deep depression and endured suicidal thoughts, but an unexpected connection with community saved her. She began the medical process to transition shortly after being outed, taking to YouTube to make a series of videos about her life story (more than 50 videos are still online — though she now calls them “embarrassing”). The response surprised her. The transgender community crowned her as an elder and began asking her for advice about transitioning later in life. Even though Rose was still navigating things like hormone therapy, facial feminization surgery and her first sexual experiences while out, helping others through sharing was therapeutic. The tone of the videos shifted to humorous chatting as Rose filmed herself baking bread. She regained confidence and was reborn with a purpose: to support the LGBTQ+ community.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

Rose’s newfound online presence united her with the trans community, but she didn’t expect it to lead her back to the male-dominated neon industry. Since being pushed out of the family business, Rose bent the occasional neon for hire but mostly survived by selling everything she owned. In 2015, she received an unlikely message. An acquaintance was in too deep on a neon job and needed highly trained help. “He got ahold of me on the internet and said, ‘Hey, Roxy, we need your help. There’s too much neon and no one qualified to do it. Get back in the game,’” she said.

A neon art piece by Roxy Rose, reading “Stop Transphobia,” hangs on the wall of her workshop.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

Roxy set up a shop in her garage and got back to bending full-time. The friend who recruited her was working for Lili Lakich, neon artist and co-founder of the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale. For a paycheck, Rose began bending Lakich’s art pieces, but her focus was discovering her purpose as not just a signmaker but an artist herself. Some of her first pieces incorporated road signs with neon lettering that spells out “Stop Transphobia.” Other works reference Black Lives Matter and the rallying cry “Respect Existence or Expect Resistance.”

The neon industry has had just as many twists and turns. The noble gas neon was first isolated by British chemists at the turn of the 20th century. Shortly after, French inventor Georges Claud debuted neon for use in business signage at the Paris Motor Show in 1910. One of the first neon signs on the West Coast was commissioned for Packard Motors in the early 1920s; it remains in use for the Packard Loft apartment buildings in downtown Los Angeles. By the 1930s, neon had taken over the United States, fitting into the Art Deco design movement and bringing a classy, futuristic feel to businesses.

Roxy Rose, in front of a neon art piece.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

After World War II, neon signs, known for drawing in customers, were used as a tool to boost the economy. Neon glass blowing schools popped up and were filled by veterans receiving job training via the GI Bill. Tied up with the vehicular culture of the burgeoning West Coast, neon’s popularity grew as car and commuting culture increased. As the economy stabilized, families began moving to the suburbs, away from epicenters of neon.

By the 1960s, moral panic induced a retreat to family values and, in turn, neon became less favored. Known for its mass presence in urban epicenters like Times Square, neon became associated with the underbelly of nightlife. Around this time, neon as a fine-art medium emerged. Some upscale cities, including Palm Springs, introduced anti-neon ordinances so as to not taint their image. In 1983, Glendale adopted an anti-neon law and required businesses to replace their “garish” neon signs with backlit plastic. While neon signs are now allowed in Palm Springs and Glendale, both cities regulate the size and number of them.

Once public perception and values began to shift, neon was due for a comeback around the 1990s. But this time, there was a cheaper alternative: plastic LED signs that look nearly the same to the untrained eye.

“It’s kind of like leather and pleather,” Rose said, comparing plastic LED and real neon. “I wear pleather, but I love leather. I also love shopping at thrift stores, and on the rack are pleather jackets, and they’re all fallen apart. Then there’s the leather jackets that are 10, 20, 30 years old and they’re perfect.”

“There’s that value added from the human element of neon,” she added. At all phases of the neon evolution, neon signs have been hand-blown and bent over fire by skilled tradespeople. The result is a one-of-a-kind, handmade piece with a shelf life of up to 100 years. The price reflects that: A custom sign can easily exceed $1,000.

Most neon businesses shut down as plastic signs took over in the 2000s. It was only because of Alert Lighting’s movie industry clientele, which commissioned signs for film sets, that Rose’s family’s business was able to survive.

Roxy Rose in her North Hollywood workshop.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

Rose’s workshop, full of neon signage.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

When Rose reentered the neon business in 2015 on her own, the landscape had shifted. Neon wasn’t mainstream, but the medium was appreciated and preserved by private and public institutions. Universal CityWalk and Las Vegas’ Fremont Street both have regulations requiring a percentage of their signage to be real neon, often done in the style of the street’s original signage. Rose has made signage that shines at both locations. Glendale’s Museum of Neon Art opened in 2016 (it started in downtown L.A. in 1981 and later moved to Glendale) and the Neon Museum in Las Vegas was founded in 1996. Both aim to educate people about the scientific and artistic history of neon and to preserve neon signage and art.

Despite that, highly skilled neon glass blowers like Rose, who still follows her grandfather’s methods, are disappearing. “There are still people alive today that insist they can tell my grandfather’s bending just by looking at a piece of neon. My grandfather’s style was tight, strong and consistent,” said Rose. Outside of private art colleges that teach neon as a fine art medium, the only way to learn neon glass blowing as a trade is through an apprenticeship or workshop.

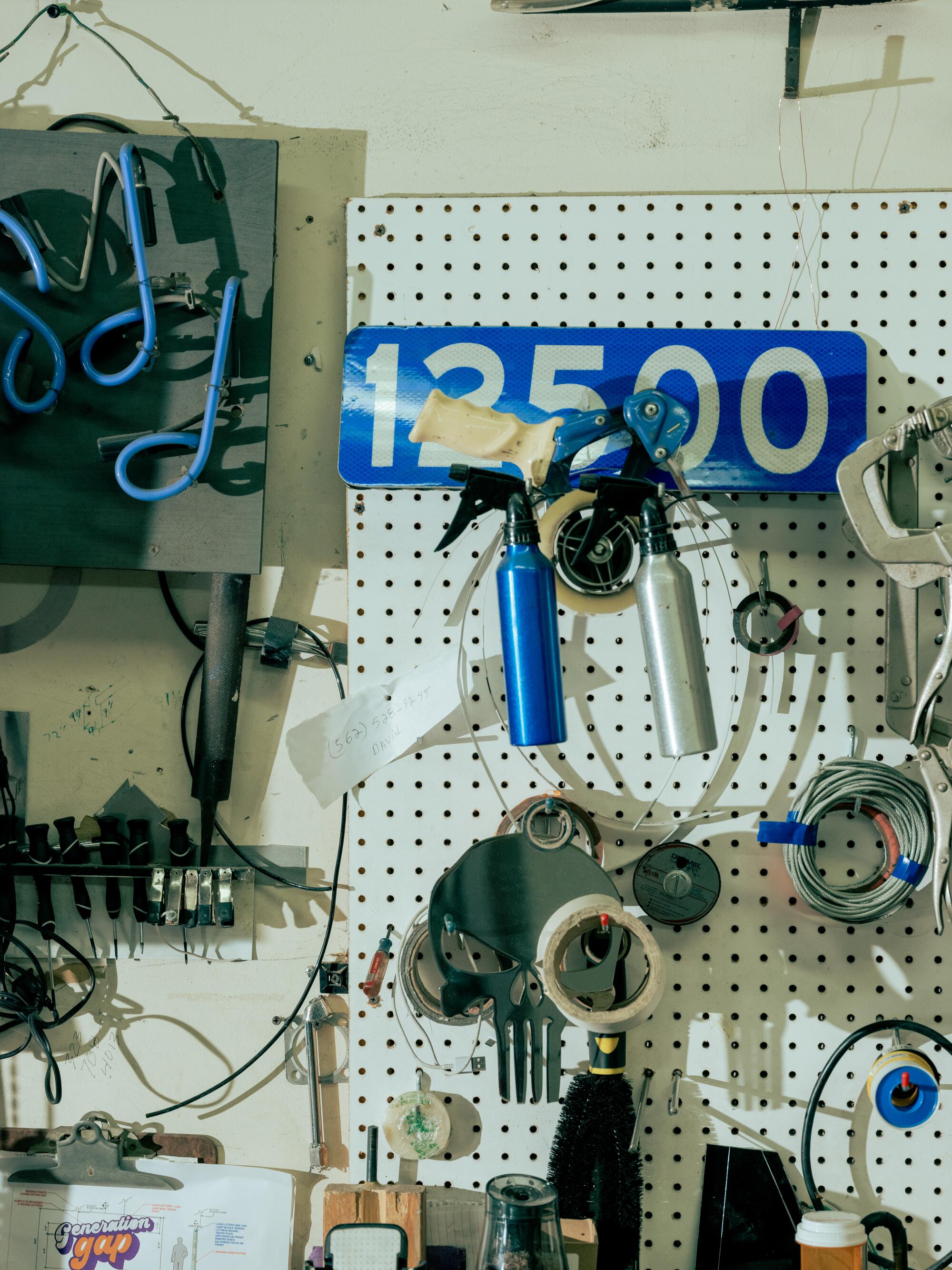

Equipment in Roxy Rose’s workshop.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

Tyler Kensek, a neon glass blower and educator who teaches at the Museum of Neon Art, was mentored by Rose. “Neon glass blowing is a heavily guarded trade. It’s very rare to find apprenticeships as most businesses want to keep it in the family,” said Kensek. “Some people learn through night and weekend workshops and go on to make fine art and the occasional commission but typically lack the precision of a true sign maker. Most people who take my classes are wealthy tech and entertainment workers who aren’t looking to take commissions from restaurants.”

Rose is optimistic about the state of neon and happy to share her grandfather’s methods. “Neon will never be the primary light source for signs as it once was in its heyday, and that just suits me fine,” she said. “Neon has been elevated in status to an art medium, and art never goes out of popularity. So I’d say the future of neon is a very bright one.” She has moved from teaching neon classes at the Museum of Neon Art to teaching classes at her own organization, the Neon Preservation Society, at her North Hollywood studio. Founded in 2023, the staff is made up of entirely LGBTQ+ community members.

These days, Rose balances crafting fine art with bending signage for businesses. Her art has been shown at the Museum of Neon Art and San Francisco’s Tenderloin Museum. She sells her work and takes commissions but only works with buyers she personally approves. As an act of activism, she often displays her work in public settings, including setting up her “Stop Transphobia” stop sign pieces in front of Chick-fil-A in Glendale. “There have been times I have been met with negativity when displaying my protest neon artwork in public. But that’s the point isn’t it?,” Rose said. “I’m not there to make trouble, but I am there to make people think and question and to let other trans, nonbinary and gay people know that they are not alone.”

Roxy Rose.

(Chris Behroozian / For The Times)

Rose shares both her work process and her thoughts on anti-trans legislation to her nearly 50,000 TikTok followers, but she feels best when she’s in the zone working in solitude. “I like the peace blowing neon glass brings me these days. In fact sometimes I think, just put me in a room, in a house, on top of a hill and let me blow glass all day long, alone. I’m kinda like Edward Scissorhands in that sense. Of course, his hands were much prettier,” said Rose.

Back outside her studio, Rose has her latest art piece hooked up to the generator of her giant red pickup truck. The 5-foot-wide, three-dimensional waving American flag features a meticulously hand-blown and -bent mantra: “Being transgender, gay, or expressing yourself in any way without the fear of persecution is as American as it gets.” On the day I came to her shop, she had plans to park the truck in public view in the center of the small, religious Bakersfield-area town she lives in.

“There were no negative reactions,” Rose said after returning to her studio with the flag art piece. “Several positive reactions. Take that, Jason Aldean.”

[ad_2]

Source link