[ad_1]

On a warm summer evening, the backyard of a Melrose photo studio was transformed into a moody mah-jongg parlor with a Wong Kar-Wai aesthetic. Amid the neon red lighting and painted lanterns, Gen Z and millennial Asian Americans sat in groups of four playing friendly but fierce rounds of a game known as China’s national pastime.

It was the latest party thrown by Mahjong Mistress, four friends who want to teach others to play the nostalgic game. Their mah-jongg parties, dubbed East Never Loses, are avant-garde scenes for Angelenos eager to embrace a game embedded in their heritage.

Mahjong Mistress is run by Abby Wu, left, Angie Lin, Susan Kounlavongsa and Zoé Blue M.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

A young crowd plays mah-jongg hosted by Mahjong Mistress.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

While there were players drinking baijiu and gossiping as they shuffled tiles — traditional mah-jongg moments — a modern “third culture kid” spirit enveloped the event. Attendees blended modern variations of traditional East Asian and Southeast Asian attire, like an unbuttoned sleeveless qipao worn as an overcoat. Numerous people sported merch from the fashion-forward ping-pong club Little Tokyo Table Tennis. There were a mix of newbies, like myself, and those who had grown up watching family members play the game. Now and then, delighted shouts of “Peng!” punctuated the atmosphere as players made special matching sets.

“This new wave of us playing this game has been feeling really pure,” says Susan Kounlavongsa, one of the organizers. “We would post [Instagram] Stories and stuff. Friends would be like, ‘Oh, my God. I want to learn how to play too.’ It’s just kind of been this domino effect of everyone wanting to come together.”

Kounlavongsa, Angela Lin, Zoé Blue M. (who uses an abbreviation of her surname to separate her artistic work and personal life) and Abby Wu call themselves Mahjong Mistress as a way of subverting Western objectification of Asian femmes. The name is an ode to “beautiful, talented women,” they say, and it’s sexual and powerful on purpose.

Mah-jongg, long associated with the Chinese-speaking diaspora, or Sinodiaspora, has expanded to an audience beyond its country of origin. There are several ways to play this game with 144 tiles; Japanese, Filipino and Cantonese styles each have their own rules. A Taiwanese style, which is simpler and easier for beginners, is taught at the East Never Loses parties.

The mistresses recruit volunteers like Eric Kwok to help them teach mah-jongg to the crowd, which varies from two dozen to three dozen players at a time. The 27-year-old engineer wore mah-jongg-inspired earrings embossed with orchid and plum flowers as they hopped from table to table, offering guidance and encouragement. They’ve seen a resurgence of interest in the game among their peers, even beyond the Mahjong Mistress events.

Eric Kwok shows off their mah-jongg-inspired earrings.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

A Mahjong Mistress event, in full swing.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

In New York, parties combining food, music and the game include the Food Mahjong Club and the Green Tile Social Club. Fans have theories as to why the game is having a renaissance. Perhaps it was spurred by the heightened awareness of Asian American cultures following pandemic violence and calls to “Stop Asian Hate.” Or perhaps Hollywood has played a role. “Crazy Rich Asians” features an iconic scene where Constance Wu’s and Michelle Yeoh’s characters face off over mah-jongg. And perhaps a new crowd of players is rehabilitating the game’s reputation after a long history in gambling circles.

“It’s a game that has historically been used in communities, specifically immigrant communities, Chinese, Cantonese and Jewish, specifically, in America to bring people together,” says Lin. “Mah-jongg is also something that is really nostalgic for all of us.”

Lin, who redistributes antique vinyl for music label Light in the Attic Records, says her “archival anxiety” drives her fascination with mah-jongg. It’s in her nature to pay attention to how Mahjong Mistress is providing a space for the past, present and future to collide. She loves to talk about how mah-jongg is often mischaracterized as an ancient game played by Chinese emperors when it was really invented in the mid-1800s. She sees parallels between the exoticization of the game and the perpetual “otherness” that Asian Americans have faced.

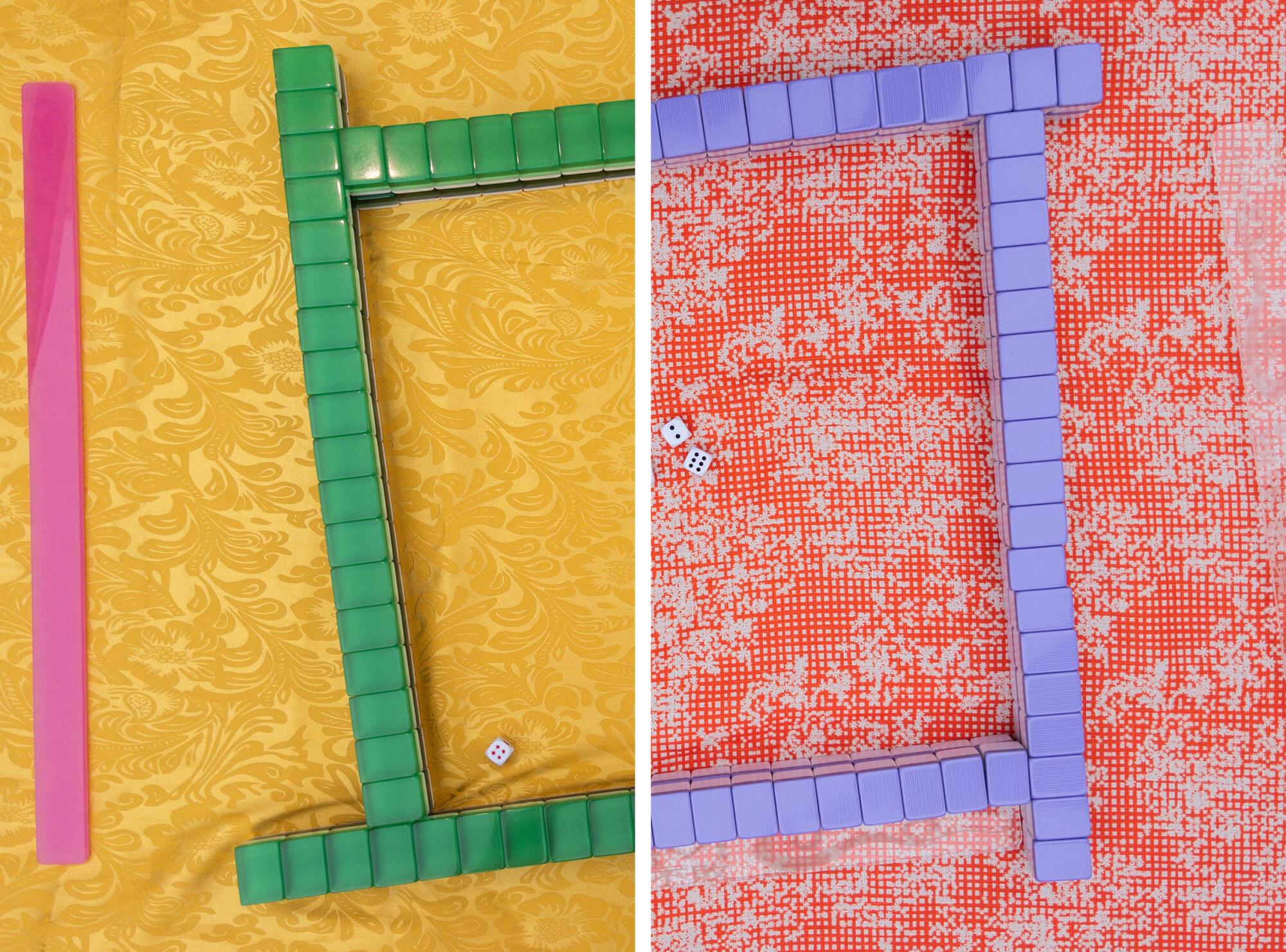

Mah-jongg tiles, on two different tables, ready for the next game.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The mistresses use their artistic skills to shape their events. Wu is the brains behind the logistics and budgeting. By day, she is a video producer with the Asian American music label 88 Rising. Lovingly called the “Angel of the scene,” Kounlavongsa taps her expansive L.A. network to help pull off the parties. She also manages NTS Radio’s L.A. studio. Zoé Blue M., who’s shown her fine artwork in Hollywood’s buzzy Jeffrey Deitch gallery, painted the backdrop for the party’s photo booth.

The Mistresses also reflect the tapestry of Asian American identity: Kounlavongsa is Laotian American; Zoé Blue M. was born in France to a French father and a Japanese American mother and raised in Los Angeles; Wu was born and raised in China; and Lin grew up in North Carolina, but as an adult lived in Taiwan, where she learned to play mah-jongg from locals. The name of the party, East Never Loses, is a reference to a chain of mah-jongg shops Lin used to frequent in Taiwan called Dong Fang Bu Bai (東方不敗). But one could also interpret it as hinting at the subversive power of playing a game of Eastern origin in the West.

A tie is settled with arm wrestling between Tiffany Chung, left, and Chris Nguyen. Nguyen won.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s a very special and unique time for what it is to be Asian American and forming identity without being in the white gaze,” urban planning engineer Katherine Lee says between games. “My friend describes it as FUBU, for us, by us.”

Lee grew up between the San Gabriel Valley and East L.A., living in Monterey Park and attending Boyle Heights High School. Despite being surrounded by Asian Americans, she felt a dearth of representation in mass media on a cultural level in the U.S.

Mahjong Mistress parties are prompting self reflection and having ripple effects. Jeffrey Tang, a bicoastal creative director for water advocacy nonprofit DigDeep in L.A., was inspired by Mahjong Mistress to start his own food pop-up, Mr. Jong, to connect people over traditional family-style meals. He believes the success of parties like Mr. Jong and Mahjong Mistress is driven by a desire to find new ways of connecting outside the technology that dominates young people’s social lives.

“There’s all these little pockets trying to create their own little communities, trying to find each other,” Tang says. He jokes that he learned to play mah-jongg by “taking money from the aunties.”

An “East Never Loses” sign hangs on the wall during a Mahjong Mistress event.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

So far, Mahjong Mistress has hosted three East Never Loses parties; all have sold out and have had wait lists. The group has received calls for brand deals and invitations to teach in corporate settings.

The parties feel warm — people make new friends or catch up with old ones — but this last one cost $35, a jump from the original free. There are challenges to hosting an event of any scale without funding. How do you rent space and pay photographers, musicians and DJs for services? The mistresses talk about the party as a labor of love, calling in favors from friends. They hope future parties can be free if they can find sponsorship partners. Lin hopes that one day, the group can collaborate with the Chinese American Museum to further educate players on the history of mah-jongg and Chinese Americans.

With enough strategy and luck, you might have a winning hand and make a new friend. Winning is fun, but making connections is the true purpose of Mahjong Mistress.

For information about future East Never Loses parties, follow Mahjong Mistress on Instagram.

[ad_2]

Source link