[ad_1]

In a second-story room in Los Feliz’s Philosophical Research Society, about a dozen people sit in a circle. Many of them are here for the first time and not entirely sure what to expect. The sandwich-board sign in the courtyard below offers only a cryptic hint: “Welcome! Death cafe meeting upstairs.”

As the group settles in on this Thursday afternoon in May, organizer Elizabeth Gill Lui lays out the only two directives: “Have tea and cake, and talk about death.”

Lui, a 73-year-old artist who wears chunky jewelry and bold glasses, starts by reading a passage from musician Nick Cave’s recent memoir. It’s about how, in the face of staggering grief, speaking and listening can be a form of healing — which is ultimately what Lui hopes will transpire over the next couple of hours, in this room decorated with patterned carpets and tall bookcases.

The tradition in Southern California has long been about the journey. Making the most of the journey creatively, playfully, intellectually. That’s what I also like about the death cafe.

— Elizabeth Lui, artist and organizer of a twice-monthly death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society

To initiate the exchange, she instructs the group to “go around in a circle and say what brought you to death cafe.” It’s a simple enough question, but one that elicits complex, deeply personal responses. Some attendees say they’ve come because they’re struggling with how to care for aging parents, or because they lost a loved one during the pandemic. Others have recently been through a life transition — a move back home, a college graduation, recovery from an illness. Or they’re wrestling with anxieties about their mortality. No matter the reason, everyone seems to be seeking some form of comfort, connection and community.

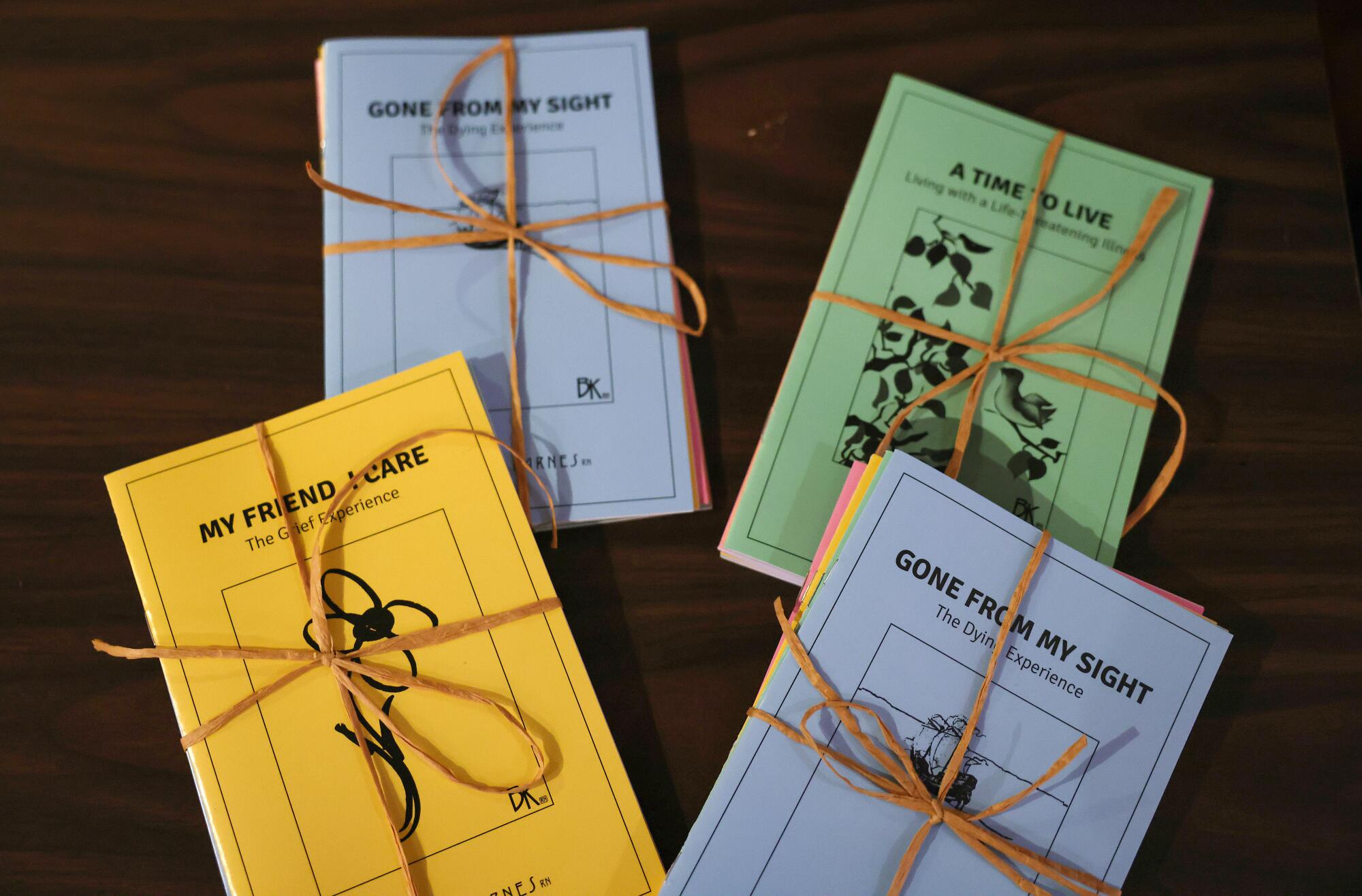

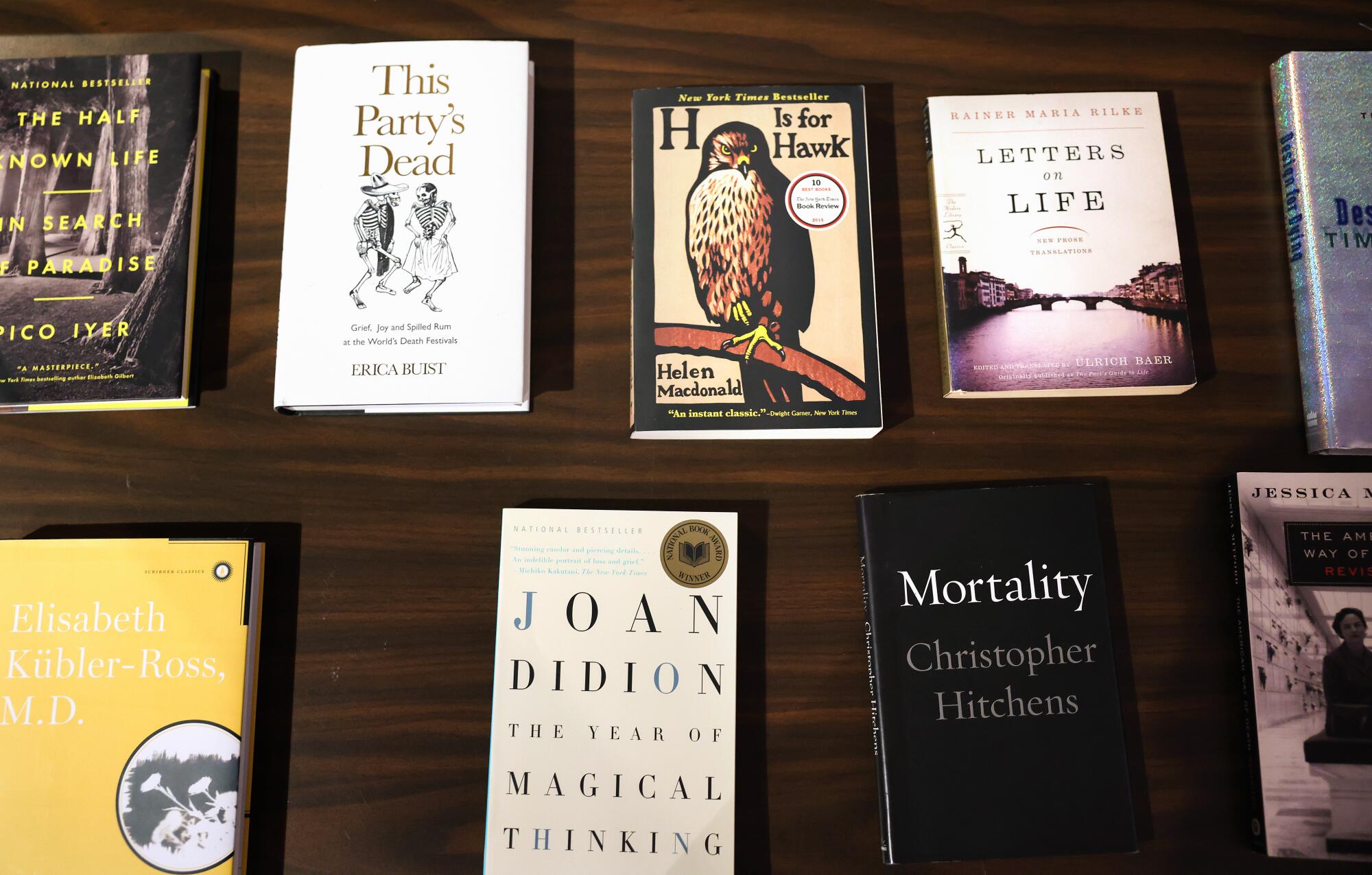

Reading material suggested by Elizabeth Gill Lui, who hosted a death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society.

“The tradition in Southern California has long been about the journey. Making the most of the journey creatively, playfully, intellectually,” Lui tells me in the Philosophical Research Society’s regal library. “That’s what I also like about the death cafe. It has this edge of humor to it. If you’re at a dinner party and it’s boring, you can just say, ‘Have I told you about the death cafe I go to?’ and everybody just laughs. It’s such a great entree to the conversation.”

Lui’s twice-monthly gathering is one of several death cafes that have sprung up over the past two years in Los Angeles. Heavy Manners Library, an art space and lending library specializing in independent books and zines, holds one every other month. Its organizer, Emily Yacina, has made a habit of bringing doughnuts for the mostly 20- and-30-something tattooed crowd. Artist Ailene deVries held a death cafe in April at Gorky, an Eastside feminist collective that hosts workshops and pop-up events. North Figueroa Bookshop in Highland Park announced its first death cafe last summer, led by death doula Hazel Angell. A collaged flier for the meeting showed a skeleton hand clutching a butterfly above a succinct description written in a Gothic font: “A group discussion of death with no agenda, objectives or themes.”

The agendaless ethos of the death cafe was developed in 2011 by Jon Underwood. The Buddhist student and former government worker, then 38, is widely credited with hosting the first modern death cafe at his home in East London. He was inspired to organize it after reading about Swiss “cafe mortels,” gatherings designed by sociologist Bernard Crettaz in 2004 to break the stigma around talking about death.

Underwood died unexpectedly in 2017 due to complications from leukemia, but the movement he kickstarted remains very much alive. A website maintained by Underwood’s mother and sister includes a how-to guide for those looking to start their own death cafe, as well as a directory that lists more than 18,000 death cafes around the world.

Greg Golden, 73, center, shares his experience beside fellow death cafe participants Danielle Tyas, 23, left, and Haley Twist, 32, right, at the Philosophical Research Society.

Megan Mooney, a clinical and medical social worker who serves as a volunteer spokesperson for Underwood’s umbrella organization, says she’s seen an increase in death cafe listings since 2020.

“COVID really made people have to face their own mortality,” she said in a Facebook message. “There was no escaping it. …There was a huge demand for people wanting to talk about death for the first time.”

That was certainly true for Lui, who says the “pervasiveness of death” during the first couple years of the pandemic led her to get certified as an end-of-life doula in March 2022.

“I really was alarmed by the fact that we couldn’t form a consensus on how to deal with the pandemic and deal with the widespread phenomenon of this many deaths,” she said. “I don’t think the seriousness of it was something that we were even able to grasp because we avoid this topic at all costs.”

Though Lui’s death cafe may be the most frequently held one in Los Angeles, it’s not the county’s first. Hospice social worker Betsy Trapasso claims that distinction, after having launched a death cafe from her home in Topanga Canyon in 2013.

“It’s not a support group. It’s not a grief group,” Trapasso told The Times that year. “My whole thing is to get people talking about [death] so they’re not afraid when the time comes.”

During the event, Trapasso asked the group of aging professionals to inhale some lavender oil to relax at the start of the session. (Though she no longer hosts a death cafe, she maintains a Facebook page where she posts articles and events related to aging, grief and end-of-life care.)

Participants sit in a circle at the death cafe.

More than a decade later, there are no bongos or essential oils at L.A.’s latest wave of death cafes and, most noticeably, their attendees skew younger. At the Thursday and Saturday sessions I attended at the Philosophical Research Society, most people were in their 20s, 30s and early 40s. At Heavy Manners Library on a Tuesday night, the group would not have looked out of place at a music show at the Echoplex down the street.

Lui sees the attendance of the millennials and zoomers at her death cafes as evidence of an unfortunate reality: Younger generations are experiencing the loss of loved ones. Some of them have cited suicide, alcoholism and drug overdoses as the cause.

“Young people are being exposed to friends dying, and more often than I think people realize,” she said.

Yacina, who leads the death cafe at Heavy Manners Library, is one of them. The 28-year-old indie rock musician says a good friend of hers died during her sophomore year of college, and she found the experience isolating, profound and “identity-forming.” Then, in 2021, she mourned the death of yet another friend, about whom she later wrote a song. Yacina said she realized “there’s no escape to people dying, and in fact, it’s actually the one true thing that we all can count on.” It led her to wonder: “Why don’t we talk about it more?”

Upcoming L.A. death cafes

She organized the Echo Park death cafe in June 2022, just a few months before Lui started one in Los Feliz. Like Lui, Yacina had recently gotten certified as an end-of-life doula, and the pandemic had planted the idea of death more firmly in her consciousness. In a phone interview, she recalled worrying that she could lose her parents to COVID-19.

“It was such a scary feeling, but the truth is, you could lose anyone at any time,” she said.

It’s a truth that deVries, the 27-year-old artist who recently held a death cafe at Gorky and plans to hold another in Long Beach this summer, had to learn the hard way.

“When I was 18, my partner just suddenly passed in a very traumatic way, so I wasn’t really sure where to put the conversation,” deVries said. “I think the death cafe was the first time that I felt I had a container to express my interest.”

Reading material suggested by Elizabeth Gill Lui.

Sara Alessandrini, 35, listens closely as another participant shares during the death cafe.

Not everyone who attends these events has experienced a death in their family or community. Some attendees instead see death as a potent metaphor for life’s big changes and all the grief that comes with them.

“It also helped me with living life in the moment and letting go of certain things,” said Sara Alessandrini, a 35-year-old filmmaker who attends Lui’s death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society.

When it’s her turn to share her reason for coming to the Thursday afternoon group, Alessandrini announces to the group that she wants to reflect not on the death of a person but of her childhood. She talks about boundaries and healing. It prompts others to chime in, openly sharing stories about their upbringings. When the conversation comes to a pause, Lui offers some warm advice to Alessandrini: “I think you need to protect yourself even better than you think you’re protecting yourself.”

Lui often takes on a maternal role in the group. During one of my visits, she asks for an attendee’s phone number so she can text them a message of support on a day they say they’re dreading. At a separate session, she gets up from her chair to console someone in emotional distress. After the meetings, she emails death-themed book and movie recommendations to newcomers, who often comprise the majority of attendees. Timothy Leary’s “Design for Dying,” the Oscar-winning Japanese drama “Departures” and the Sundance-winning documentary “How to Die in Oregon” are all on her list.

Since many of her attendees are artists themselves, she sends out invites to their events, which often intersect with ideas about death. Recent examples include an online radio program featuring songs for funerals and a solo show about grief debuting at the Hollywood Fringe festival this month.

Lui sometimes signs her emails: “Hope to see you when it fits.” She wants attendees to know there’s no obligation to return to her death cafe. Even so, the group can occasionally get large and unwieldy. At one recent death cafe, Lui recalled, there were 30 people, “and that was a little too much.”

Michael Allison, 62, laughs a little while sharing with the group of participants in the death cafe.

The death cafe can sometimes feel like group therapy. But Lui makes no claims to being a therapist. “I think in a good way, we’re not therapists,” she told me. “Because we’re not just nodding and listening and letting them figure out their own truth. We actually have some ideas about where you find meaning in your life.”

At the Thursday afternoon death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society, everyone has so much to say that the conversation stretches for hours. Toward the end, it becomes loose and playful, resembling a late-night heart-to-heart. Between bouts of tears and laughter, someone asks: “Do you think you know that you’re dead after you’ve died?” Another poses a question: “Is it just me, or has anyone else ever wondered if your dead parent can see you when you’re having sex?” The room giggles, and it reminds one attendee to share her own story about her deceased mother.

At some point, Lui asks whether anyone knows the time. It’s 6 p.m. — meaning the death cafe has stretched on for four hours, twice as long as scheduled. Lui frantically apologizes, but nobody seems to mind. They hang around, talking and eating cupcakes.

“Maybe we need a weekend retreat or something?” Lui suggests. But even a few days wouldn’t be enough to contain everyone’s questions about one of life’s greatest mysteries. For now, her cafe will have to suffice.

[ad_2]

Source link