[ad_1]

Before I set up the Wi-Fi-connected, AI-powered Bird Buddy smart bird feeder, I didn’t spend a whole lot of time thinking about the birds in my backyard. Now I can’t stop wondering if I’m violating their privacy rights.

It didn’t happen right away. At first, I was blinded by the novelty of the $269 solar-roofed gizmo, which arrived on my doorstep last fall as a gift from my father-in-law. I was impressed by how it used artificial intelligence to identify — and introduce me to — the various species stopping by for a bite. The first visitors were house finches (which have a good memory and nine- to 10-year lifespan, the app informed me), followed by California towhees (described as “territorial and feisty”).

The Bird Buddy Wi-Fi-connected, AI-powered bird feeder ($199 as shown, with solar-powered roof, $269) photographs and identifies birds and then sends notifications to a smartphone app.

(Bird Buddy)

I remember feeling a twinge of excitement the first time my phone pinged with a “Look who’s here!” alert (it turned out to be a squirrel), an adrenaline rush that seemed to intensify with each successive alert. I marveled at how quickly my feeder became a gathering place for urban avians and how the app kept track of their visits with a cartoonish, odometer-like graphic. As of this writing, it’s logged 194 house finch visits, 83 California towhee drop-bys, 5 squirrel sorties and a lone pine siskin pop in.

The app also made sharing the captured photos and videos to the wider Bird Buddy community — and my own circle of friends — as easy as a few button clicks. In no time at all, I was proudly blasting out photos of the birds bellied up to my backyard buffet; winged clowns captured comically mid-snack with a beak full of seeds with heads cocked quizzically staring into the camera lens.

A house finch stops by a Beverly Grove bird feeder for a bite.

(Adam Tschorn via Bird Buddy)

A few months into my new hobby as a backyard birder, I discovered that, with a few simple clicks (and the requisite granting of permissions on the other end), I could monitor not just my own Bird Buddy but also my sister-in-law’s in Ohio. Soon, my feeder feed was filling with black-capped chickadees, dark-eyed juncos and tufted titmice from 2,000 miles away. Peering beyond my own backyard made me feel powerful and all-seeing. It also made me feel like I might be overstepping my bird boundaries just a bit.

Then, on a cool, mid-April morning, I did something I instantly regretted. Shortly after a bright red northern cardinal winged into the Ohio feeder for the second time in two minutes and stuffed its beak, I sent its photo to the family text thread.

“He’s got a healthy appetite,” I noted. “And he’s pretty plump too!” I looked down at my phone and realized what I’d done. I’d just fat-shamed a cardinal.

After that, the excitement of each arriving-bird notification was tempered with a tiny guilt pang; the feeling that somehow I was engaging in “birdsploitation” — luring these glorious miracles of flight into my (or my sister-in-law’s) world with nothing more than few handfuls of birdseed and then mocking them by circulating pictures of their feeding-frenzied behavior to get my jollies.

A northern cardinal photographed at a Bird Buddy in northeastern Ohio.

(Adam Tschorn via Bird Buddy)

In thinking through my bird-bullying behavior, I started to genuinely wonder: Did these visitors to my backyard have a right to privacy? And if they did, was I somehow violating it by using my high-tech toy — essentially facial recognition for the bird world — to identify and track them? And if I was violating their privacy, was I somehow making it worse by sharing and commenting on the photos and videos?

The first stop on my hunt for answers was the National Audubon Society’s Guide to Ethical Bird Photography and Videography. “Luring birds closer in order to photograph them is often possible,” notes the pertinent section of the guide, “but should be done in a responsible way.”

The guide went on to explain that being responsible includes asking, “Could this be harmful to the bird?,” not luring birds using live or dead animal bait (a practice that changes predatory bird behavior), not using birdcall audio clips and keeping bird feeding stations clean, stocked with the right food and positioned with the birds’ safety in mind.

Based on that, I felt I hadn’t run afoul of the Audubon Society. I’ve got a 33-pound bag of Petco All-Purpose Seed Mix for Most Wild Birds on hand at all times. The Bird Buddy app has a built-in alert to remind me about regular feeder cleanings (and links to an instructional cleaning video), and the notion of using pre-recorded birdcalls — or live bait — hadn’t even crossed my mind.

Still, I couldn’t quite shake the feeling that I was somehow being too intrusive. So when I discovered the Mindful Birding project, whose stated goals include “encourag[ing] a practice of mindfulness among birders,” I decided to push my inquiry a little further.

That’s how I ended up on the phone discussing the privacy rights of birds with the project’s founder, Marla Morrissey.

“There are a couple different definitions of privacy,” Morrissey said as we talked through the topic. “One of them is freedom from unwanted or undue intrusion, and another one is freedom from being observed or disturbed. So there’s kind of a continuum of privacy from the least disturbance to the most disturbance.”

Morrissey said that actions like stomping around a bird’s natural habitat or using a laser pointer are examples at the more-disturbance end of the continuum, while the stealth remote capturing of the birds’ images (the Bird Buddy’s camera shutter is silent) skews toward the other. “In that case, you’d be at a pretty low level of disturbance,” she said.

However, Morrissey wasn’t about to totally let me off the hook.

“But a bigger question is how is your feeder affecting the little ecosystem around your yard?” she said. “Most feeders are for enhancing [the available] food for certain species, but you could be attracting a crow or something that could come in and gulp up everything. That would act as a kind of secondary disturbance.”

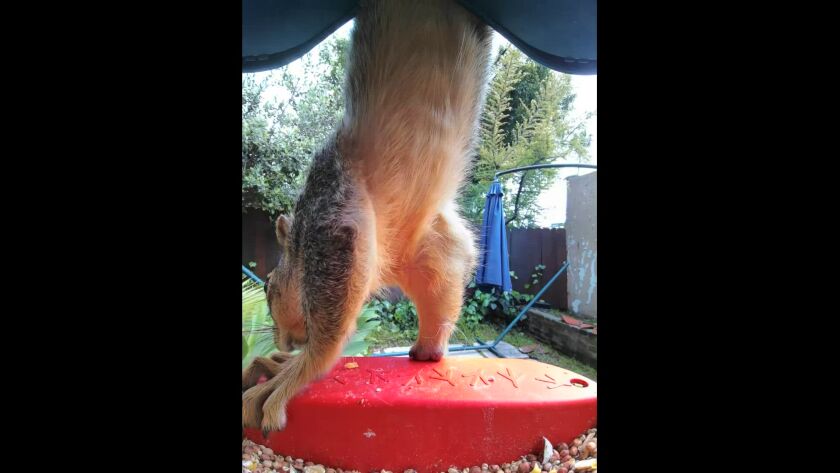

The new Bird Buddy smart bird feeder photographs and identifies birds — and the occasional squirrel — and sends notifications to a smartphone app

I immediately thought about the acrobatic squirrel that my Bird Buddy had captured — not infrequently — dangling from the roof of the feeder by its hind legs while it gorged itself on bird seed.

“So back to your question about privacy,” Morrissey continued. “I think when you put it on this continuum, if the animal is acting normally — if it’s not disturbed by you — that’s one side of it. But on the other side, you’re changing the habitat and even the proportion of different species [in that habitat].”

In other words, it wasn’t the camera part but the feeder part of my new toy that has the biggest potential to disturb the status quo for my winged dinner guests, thereby infringing on the freedom-from-disturbance aspect of their privacy rights. Fair enough. But the notion that birdfeeders aren’t the best way to provide food and habitat for native birds isn’t new. (My Times colleague Jeanette Marantos suggests a bird-friendly backyard makeover that includes growing the plants that wild birds need for food and nesting materials.) So I pressed Morrissey about the social-media-like, photo-sharing part of the experience — and how I felt guilty about publicly pointing out the plumpness of a certain cardinal.

“As far as the fat-shaming? Look, it could actually be a good thing for the bird [to be heavier] depending on the time of year!” she said.

Feeling like I was almost out of the woods, I asked Morrissey if I should feel bad about the sharing of my Bird Buddy photos online with friends or posting them to social media for the enjoyment of others (in addition to Bird Buddy’s own app, there’s a particularly active Bird Buddy owner’s group on Facebook) when all these creatures have done is swoop into my backyard looking for a bite to eat.

“I don’t know that there’s an exact answer to that,” she said. “But I don’t think you can go wrong with staying curious.

“[Birding] is a fascinating hobby,” she added. “And if it’s done well, we’re going to come out a little more on the hero side than the villain [side], right? If we don’t pay attention to all the other impacts, it isn’t impossible to end up on the villain side.”

Although I didn’t quite get the definitive answer about avian privacy rights I was hoping for, Morrissey did help me see my Bird Buddy through a new lens. By identifying the house finches, California towhees and other birds flocking to my feeder, it piqued my curiosity about the birds that inhabit the world around me. By delivering the photos and videos to my phone and making them easy to share, it’s also easily connected me with a community of like-minded enthusiasts. In short, it’s helped kindle an interest in birding.

Now it’s up to me to proceed in a way that’s mindful. Maybe that means tearing up my lawn and making it more bird-friendly. Maybe that means spending less time looking at birds on the app and more time looking at birds out in the wilderness. And maybe it means supporting a bird conservation group like the National Audubon Society or a project like Mindful Birding. But it definitely means keeping my Bird Buddy clean and well-stocked as long as it’s hanging in my backyard.

I may never be a full-fledged bird hero, but I’m determined not to end up a bird villain either.

[ad_2]

Source link